Professional audio tours combine with the power of Google Street View to provide engrossing, informative virtual visits to the Acropolis and Parthenon.

I’ve been to the Acropolis of Athens before. In fact, I’ve climbed the Sacred Rock more than once, usually on hasty visits with friends from abroad – but for some reason I’ve never gone with a guide. My memories from those visits therefore have less to do with the things I learned (which was whatever little I picked up from information signs around the site), and more to do with the heat, taking selfies, and illicitly trying to listen in on other people’s guides. I finally made the decision to not visit again unless I had enough time to take a real tour.

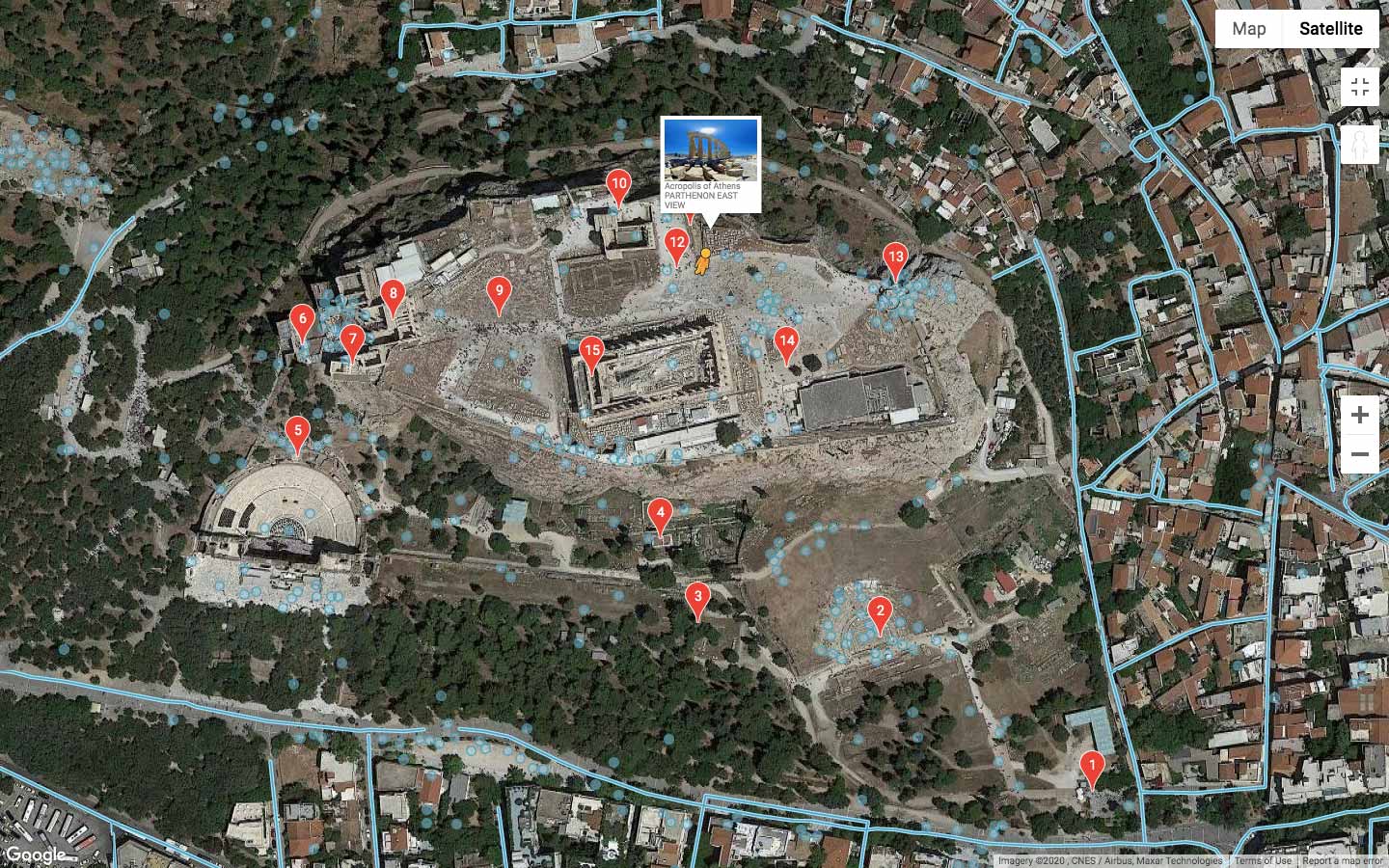

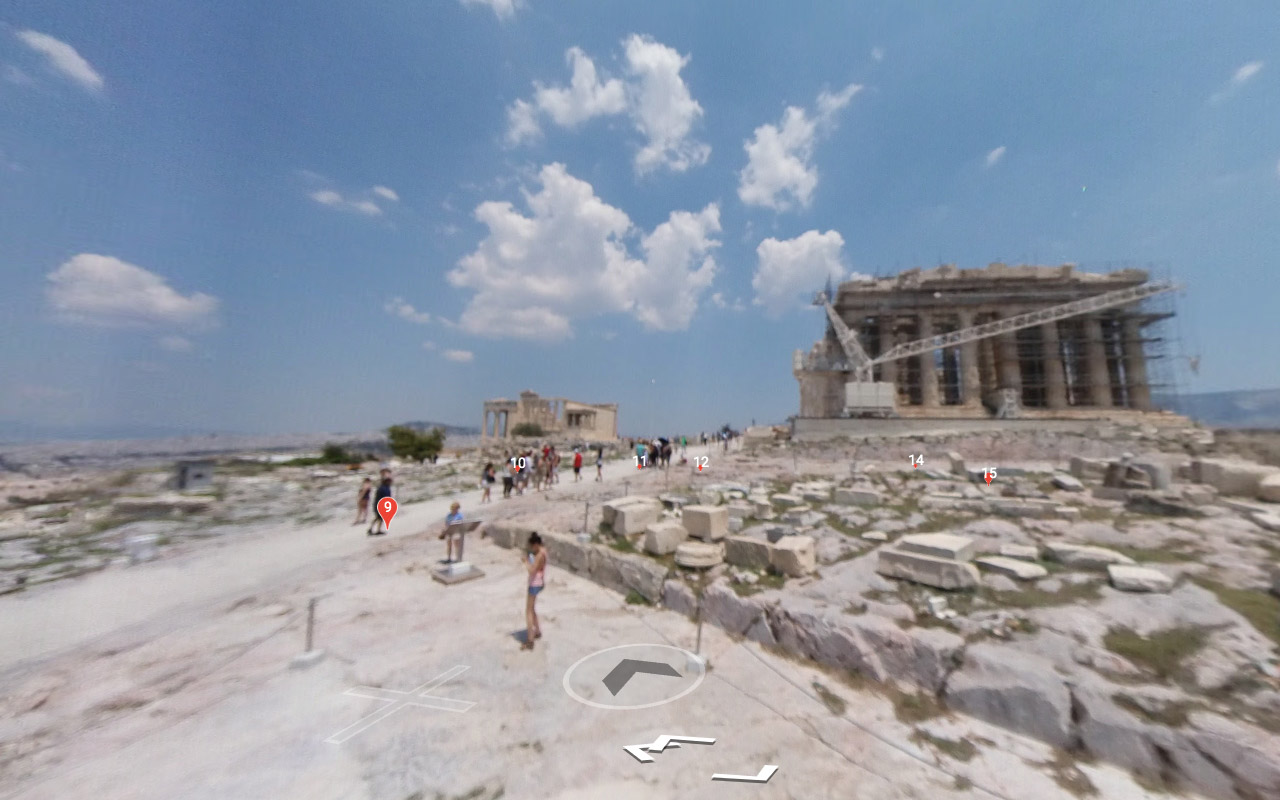

Now, the tour I’m about to take isn’t the one I originally envisioned. It’s a virtual tour, launched by the audio guide company Clio Muse just as COVID-19 has frozen tourism the world over. Combining an audio guide providing information and stories of the sites, the ancient Athenians and their gods, with the 360° images of Google Street View, it promises to be the closest one can get to actually visiting the Acropolis right now.

All one needs is time, and since that is the one thing that I – like most everyone – have on my hands in abundance, it seems perfect.

© Clio Muse

Looking at the preview of the tour on the website, the marble columns of the Erechteion shine in the sunny weather, evoking various memories of summer, travel and adventure. In my dimly lit room, in self-isolation, it does look inviting. In fact, it looks so different from my reality, I know what I have to do. I pick up my laptop and move out on the balcony.

It’s a sunny spring day and birds are chirping away. Earbuds in, I imagine I’m on pedestrianized Dionysiou Areopagitou Street underneath the Acropolis. I turn and start walking up the stone paths between the trees of the Sacred Rock’s slopes, towards the ancient citadel with all those famous temples commissioned by Pericles in the 5th c. BC. And then I press play.

The tour begins at the south slope entrance, not at the main entrance. I have never entered through here before. The voice in my headphones informs me that we’ll be taking this route in order to see some of the sights many tourists miss, before heading up to the top of the rock.

© Clio Muse

The Theater of Dionysus

The first stop is the Theater of Dionysus. I’m “standing” in the second row of the simple stone bleachers, but I learn that the real places of honor were the fancier looking marble seats in the front row. My audio guide then wastes no time before diving into facts about the cult of Dionysus, the City Dionysia festival, and the famous playwrights of ancient Greece.

The carvings in what’s left of the stage front depict the myths of the ancient god, he tells me. Zooming in, I notice a satyr, depicted as if holding the structure up and crouching under the weight. Amazingly, this artwork seems like it’s even more fitting today, thousands of years of carrying that weight later, than it must have when it was put in place. There is also a low wall in front of me, which, the voice in my headphones explains, was added by the Romans to protect the audience during the gladiator battles and wild animal fights.

Clicking the arrow for the next spots on the map, I head to the Ascleipon (healing sanctuary) via the Stoa of Eumenes; the latter, I learn, was once a 163-meter structure with two floors, built to protect theater goers from sun and rain during the breaks between plays.

© Google Street View

Asclepieion

I’m encouraged to find a spot in the shade of a tree, and as I imagine myself leaning against it, I am suddenly brought back to the reality of 2020, because this spot on the map was once a hospital. “The year was 430 BC,” the voice in my headphones tells me, “and Athens was struck by the plague, which gradually spread all across the city”. Ten years later, I learn, 25 percent of the Athenians had died from the disease, and this sanctuary and healing center was created in the honor of Asclepios, the god of medicine.

After I briefly thank technology and the almost two and a half millennia separating me from the actual Asclepieion and the ancient plague (as a good citizen I have recently learned to stay away from hospitals in epidemic times), I take some time to look around. I can see the path leading back to the Theater of Dionysus and on to the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, and I’m reminded that building hospitals next to theaters was once common practice, as watching a tragedy at a theater was considered therapeutic, and the ancient Greeks were well aware of the connection between a healthy mind and a strong body.

© Google Street View

© Clio Muse

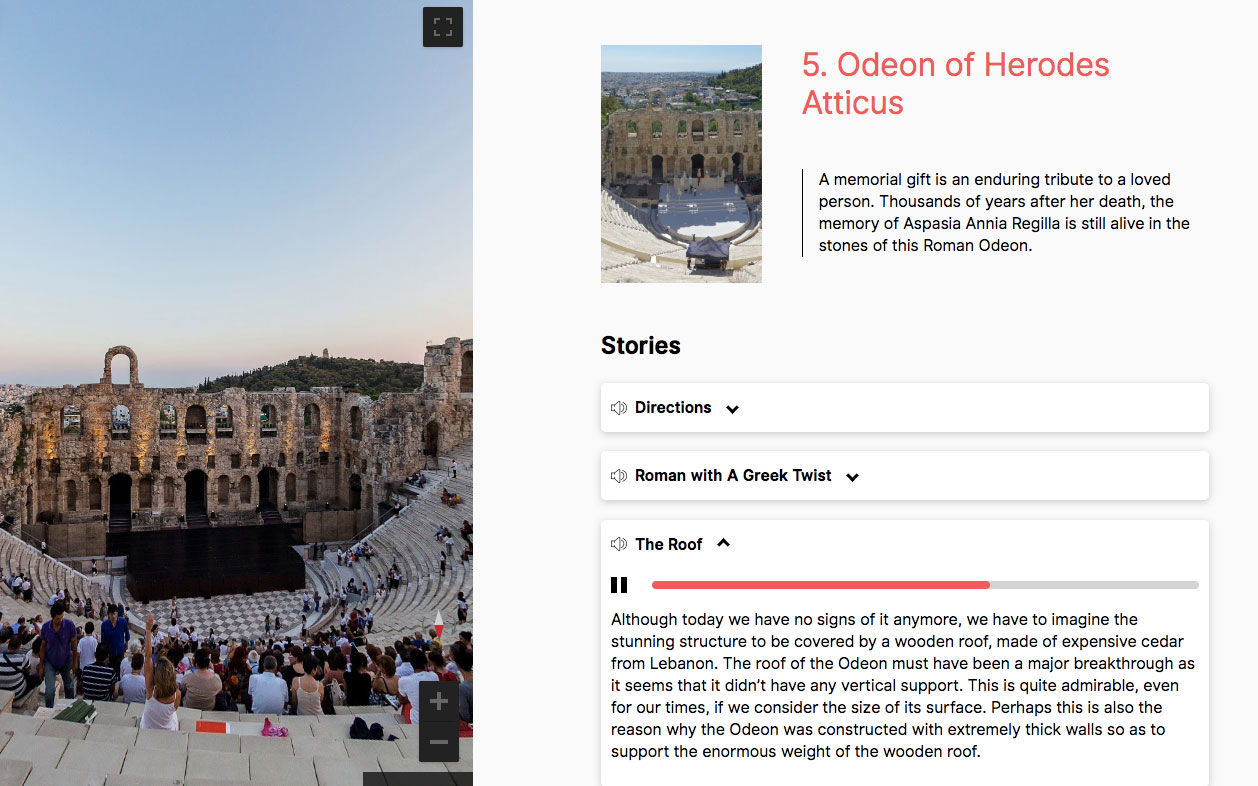

Moving on to the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, I seem to be “arriving” just in time for a play. This amphitheater looks quite different from the Theater of Dionysus. Constructed much later, in 161 AD, by the Roman magnate Herodes, it was once covered by an enormous wooden roof, and the still preserved 28-meter high back of the scene features the dynamic curves that were a popular architectural feature of the Roman Empire.

Some people have begun gathering on the bleachers below me. If this was real life, some famous play or world-known artist would likely be taking the stage soon (the theater returned to use in 1920).

© Google Street View

On top of the Sacred Rock

Finally climbing the hill, my guide tells me all about the impressive structures I pass on the way; ramps, stairs, temples, bastions and marble pedestals create an impressive landscape which, seeing it this way, looks taken straight out of a fantasy video game (and not by chance – many of those games have been inspired by Greek temples).

Reaching the height of the temple of Athena Nike, I can see all the way to the sea as I’m told the story of Aegeus, the king of Athens, who from here saw the black sails of his son Theseus’ ship as he was returning from slaying the Minotaur on Crete, and, believing that his son was dead, jumped from the nearby bastion.

Finally, coming through the Propylaea, the majestic entrance building to the Acropolis, the 360° image really shows its best side, which in this case is up. The sky-high columns and the piece of the preserved roof make you ponder how the ancients managed to build like this without modern equipment (later, I will learn all about how the marble blocks were carried with the help of draft animals, ropes and cranes).

© Google Street View

The Erechtheion

After the Parthenon, the Erechtheion is probably the most famous of the structures on the Acropolis, but looking at it from three directions on this tour, I realize that only a corner of it is usually represented in pictures (the Porch of the Caryatids). My guide takes the time to show sides of the temple I wouldn’t have been able to identify in a quiz, and points out interesting details. For example, a hole in the ceiling is noticeable at the temple’s north entrance, where Zeus is said to have struck earth with a lightning bolt to kill Erechtheus.

Another amazing thing you won’t notice in pictures: the remains of the Mycenian Palace of Athens, which once occupied the plateau just in front of the eye-catching caryatids, long before any religious temples were built on the hill.

© Google Street View

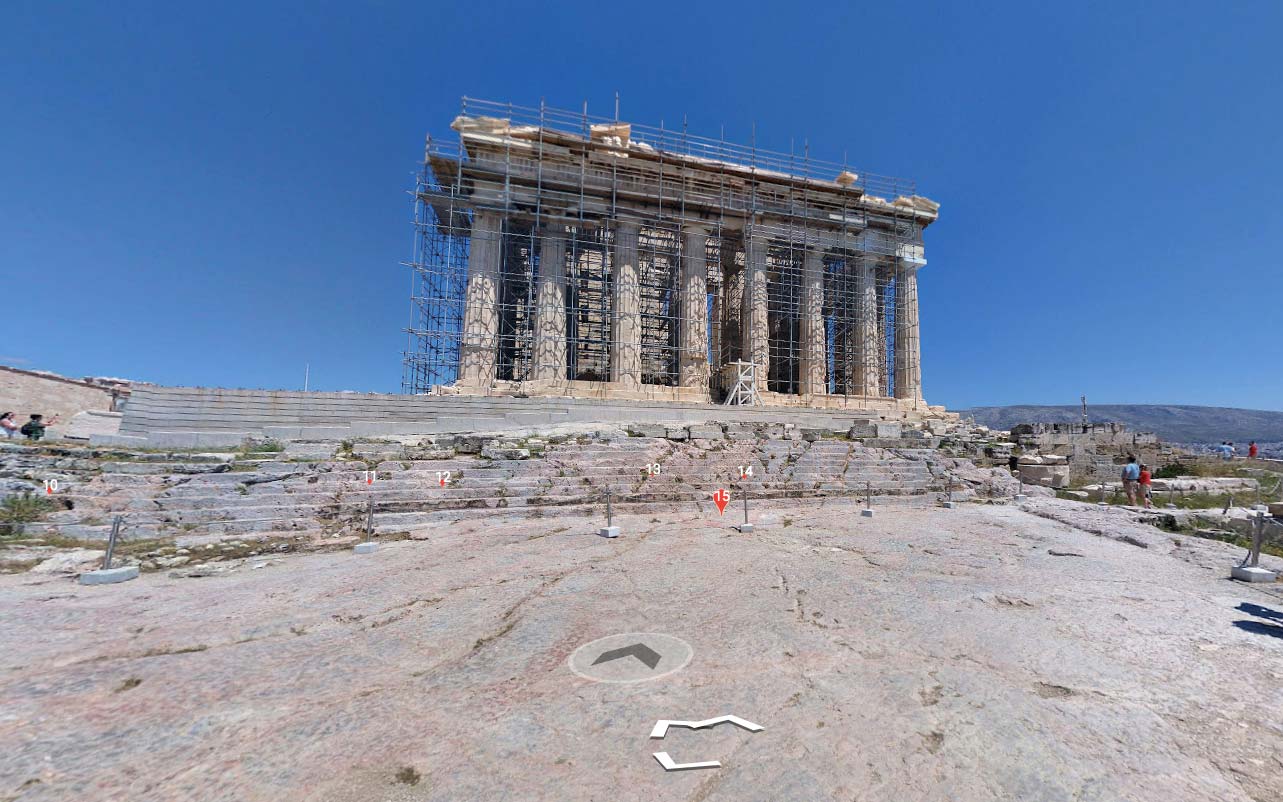

The Parthenon

Finally, the crown jewel, the temple so famous tourists are often confused about its name; is it “Parthenon”, is it “Acropolis”, are they one and the same? (It’s “Parthenon” – “acropolis” is the word for a citadel in any ancient Greek city, and this particular acropolis is the most famous because it was that of a superpower.)

Built in just nine years (447-438 BC), the Parthenon’s impressive size was necessary for it to house the 11-meter tall statue of Athena Parthenos. While the statue is long gone, my guide paints me a picture: “Made by Phidias, he used ivory for the flesh and more than 1,100 kilograms of pure gold for the clothes… The virgin supported a shield with her left hand, while a Winged Victory rested on her right hand. There was a small pool of water in front of her to provide the humidity required so that the ivory would not dry out and crack.”

© Shutterstock

Moving to another side of the temple, I’m asked to look at the famous Pentelic marble columns, and notice details like how the corner ones are thicker than the others – an intentional aesthetic choice as there was no wall behind those columns, and seeing them against the sky would otherwise make them appear thinner than the others. In fact, while seemingly a masterpiece of symmetry, there is almost no straight line on the Parthenon, but rather a myriad of optical illusions that make it seem so.

On a real visit, all the white at the Acropolis is blinding under a stark sun. On the one hand, that’ll help you remember the site as if bathing in a sort of divine light, but on the other hand will make you avert your eyes. The ancient Athenians knew this, and large surfaces of the Parthenon were therefore painted deep red, blue, gold and black.

On a virtual tour, while it can’t beat actually walking on the rock on which Pericles once stood when his temples were being built, you also don’t feel the need to look away. Instead, you zoom.

© Clio Muse

© Google Street View

Final Review

Clio Muse’s Acropolis Hill virtual tours feel like something between taking an audio tour, watching a documentary, and playing a video game. Each point begins with directions on how to get there, which makes me think the audio for the virtual tour are the same as for the regular audio tour that you can take in real life – however, the directions remain helpful even navigating via computer, as they provide an idea of the distances and what you would have seen moving from one place to another, if you were really there. Sometimes, I would have wished for clearer images, as zooming resulted in pixelated views, but overall, I’m impressed with how much I did see on this tour, which even had me noticing some details I’ve never spotted on a real life visit.

Tip: If you’re a rebel, you can, instead of following the tour from start to finish, also move around with street view using the arrows. To do so, when in the satellite view, pull Google’s Pegman to any spot on the map. Clio Muse’s audio spots will then appear around you as you get near them.

Σχόλια για αυτό το άρθρο