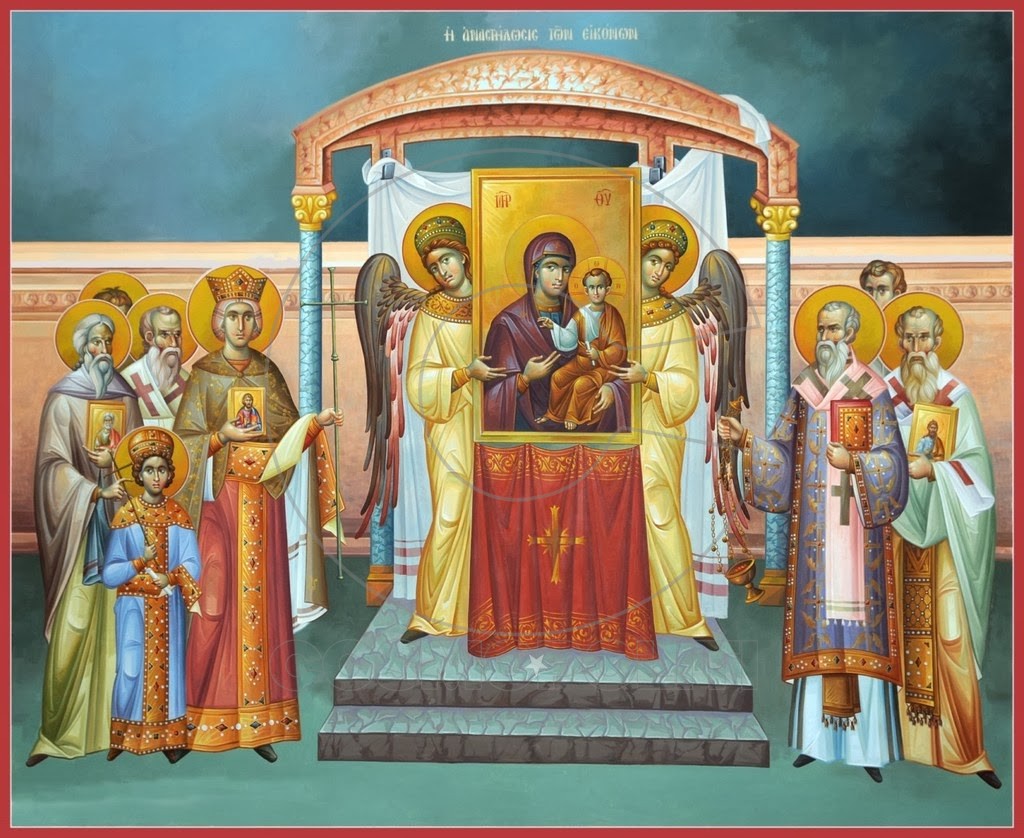

MYKONOS — The legends of Mykonos begin with tales of seduction and oblivion. The island of Ithaca, Cavafy told us in his famous poem, is more than a destination; it is a state of mind. Mykonos has come to symbolize much more than Ithaca ever meant to poets and travelers alike; since the 1950s, it has been a paradisiacal escape, a kingdom for all the barefoot kings and nowadays, a stronghold of opportunity and affluence in a bankrupt country.

There are as many lost treasures as bones buried under the streets of this greedy island that has enticed armies, pirates, moguls and tourists alike from the time of the poets to the days of Aristotle Onassis and, most recently, Starbucks. People have flocked here since ancient times to enjoy or cash in on the hedonistic promises of an island that became synonymous with beauty, pleasure and profit. Appropriately, one of the most popular beaches here is called Super Paradise.

Today, there are many names for this paradise: Manhattan of the Aegean, Isla Bonita, Rock of the Giants, island of the winds, Diva of the Aegean. While the rest of Greece is suffering the worst depression since WWII, Mykonos remains a solid castle of prosperity, a trillion-euro-private-investment that blinks from afar like the most expensive jewel of the Mediterranean: stunning villas designed by starchitects, glitzy fashion superstores, sophisticated galleries, luxurious hotels and countless A-list restaurants that surpass in service, style and prices any establishments in the rest of Greece.

These days, some liken Mykonos to a modern day Pompeii — a city of excess about to be swept away by the detritus of ash and pumice released from the volcanic explosion of the Greek economy. But, I assure you, this won’t happen; if this island enticed to death parades of Persians and, later, Arabs, Venetians and Turks, it can afford to deal with the harsh austerity that plagues the rest of the country.

“We are producing our own wealth,” a local businessman tells me. “We are a hard-working money-making-minded people that have survived many hardships. Our drive and our dream are more American than European. If Mykonos ever gained independence from the rest of Greece, it would be one of the richest microstates on the globe.”

“It has helped to put Greece back on the map again,” the Guardian noted. “Visitors have signaled greater overall satisfaction with Mykonos than Ibiza, Sardinia or St. Tropez — its main competitors.”

Despite Greece’s worsening economic odyssey this summer, Mykonos’ cashiers are filling: hotels and villas are full; during the summer months, its small airport is one of the busiest in Europe. Not surprisingly, the night of June 27, when the rest of Greece was afire with uncertainty about the referendum just called by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, the town of Mykonos glittered under an umbrella of fireworks. It was Saturday night, and the main news celebrated on the island was the American Supreme Court’s decision in favor of gay marriage.

Of course, gays were getting “married” on Mykonos long before any Supreme Court’s decision back when homophobia reigned in the rest of the globe. During the 1960s and 1970s, gays came here to feel free and celebrate make-believe weddings outside the legendary Pierro’s bar where races and classes mingled and bodies swung when the music played. The Greek Dolce Vita began on Mykonos and, as a local historian once put it, it grew into something “more Felliniesque than a Fellini film.” That was the time that it was a shame not to be gay on Mykonos and Swinging Mykonos, as much as London, emerged as a pleasant aftershock of May 1968.

“The secret of the Mykonian success is tolerance,” Anna Kousathana tells me. “Mykonos became an international paradise because of that. Provinciality was never part of the Mykonian mindset. I remember back in the late 1960s, there was a policeman here who was very strict with the tourists, especially women. He would stop them if they wore shorts and admonish them, ‘What is that? Go and change!’ Before he knew it, he was fired by the local authorities! People here never tolerated such closed-mindedness.”

Princess Soraya used to stay at Anna’s grandfather’s house and, as Anna recalled to me, “no one ever bothered with her affairs; people never call the paparazzis here, they mind their own business.” Anna, who once worked with her late husband in the American-owned mines of Mykonos, long shut now, has seen both sides of the Mykonian coin. “This island is a place of extremes. It has known extreme poverty and excessive wealth but it has never lost its humor or its beauty. Beauty speaks for itself.”

Before the age of tourism, Mykonos was so poor that its men had to take to the seas to support the families they left behind. Until one day in the early 1960s, when the boat of a Greek god approached from the West. It was not Poseidon. It was Onassis, who counted more than the 12 other gods together. With the arrival of “Christina,” Onassis’ famous yacht, Mykonos entered the orbit of a brilliant fate. Ari brought with him his Olympian crowd — his future wife Jackie Kennedy, divine mistress Maria Kallas and good friend Liz Taylor — that turned this paradise into a glamor mecca. The rest is history and part of this history is the resilient ambition of the middle-class Greek to become Onassis and spend it at Katrin’s, the restaurant that the mogul frequented on the island.

That’s how Mykonos in the 1990s, a time of global economic boom, became the West Egg of Eurogreece, a playground of the nouveau riche Athenian masters of the universe who came to the Manhattan of the Aegean to build Gatsby-esque mansions and to reenact a Greek version of The Bonfire of the Vanities. As Tom Wolfe might put it: The excess! The insolence! The bloody long cigars! The manicured Filipino maids! If the rich are different than you and I, as Nick Carraway famously pondered in The Great Gatsby, this breed of wannabe Athenian master shouted his wealth louder than the wind. The ancients had a word for immodesty: hubris. The Mykonian expression of immodest riches accelerated so fast that when it derailed, entire fortunes had gone with the wind.

The Gilded Age of Mykonos came to an end about five years ago when the Greek Gatsbies went down in their own pool of debt, vanity and deception. Ironically, the island has been doing even better without them. Despite the Greek crisis, real estate is booming on Mykonos. A Greek businessman had to sell his large villa on the island recently to pay off his immense tax debts and received a handsome 5 million euros for it.

“Mykonos functions autonomously like an independent principality,” confirms Francesca Kalamara, a thriving Mykonian real estate agent, said to me. “Ten years ago, we dealt exclusively with wealthy Greeks, and we snubbed the foreigners. Now, unfortunately, we do the opposite. The Greeks only want to sell to get rid of high taxation. Our main buyers now are Lebanese, Israelis, French and Greek Americans, and the prices we sell are competitive if not higher than places like the Hamptons or the south of France, when in the rest of Greece nothing moves.”

And yet, the island remains a haven of opportunity for the Greeks who want to do business here and cater to a global clientele. Penny Vomva, a young Athenian designer with stores on Mykonos and in Athens told me that, “By far, Mykonos is not only more profitable than Athens, but also a showcase that earns you a world reputation. If you can make it here, chances are you can make it anywhere.”

“No doubt there is no other place like Mykonos in Greece in terms of influence and exposure,” Greek-born, New York-based artist Lydia Venieri, who is the creator of Mykonos Biennale, an international symposium of art and philosophy, said to me. “Everybody likes to speak about the power of money these days on Mykonos, but we forget that this place is also about energy, history, tradition and beauty,” Venieri added. “That’s why this year’s biennale is titled ‘Antidote.’ We all need a portion of it.”

The paradox that — as Greece goes down, Mykonos goes up — is explained by the tenacity of private initiative against the odds of a dysfunctional state. The shabby state services and poor local politics of the island still reflect the failures that led Greece to the edge of the precipice. Two former mayors of Mykonos are accused of corruption (their cases are still pending), while the new one has disappointed even his most ardent supporters with his inaction. An Athenian owner of a villa complained to me that “Mykonos is the place with some of the most expensive houses in the world; yet if your house is on fire, you mind as well forget about it. The fire department is nonexistent here, and the mayor is still thinking about it.” (The mayor never responded to my requests for an interview.)

It’s not just the fire department. The state-run airport is so rundown that a hole in the tarmac withheld tens of flights the other day. On a recent visit to the Mykonos tax office, one of the most crucial of the nation in terms of incoming tax revenue, I encountered lines of exasperated taxpayers queuing for hours to be serviced by an understaffed bureau.

“The miracle of Mykonos is all a result of a private effort; any serious businesses here always knew not to count on any state support,” says Michalis Sigounas over lunch. Seven years ago, Sigounas and his partner, the German-born Carsten Stehr, opened a small bar at the edge of the port where the waves splash and water sprays people’s faces. “People feel free here,” he adds. “We were tired of the 1990s excess. The Pierro’s culture was done, and we decided to launch a new bar in 2008 which was the beginning of yet another crisis. We did surprisingly well.”

“This season is even better than last year,” admits Stehr. “But we deal with the difficulties like everybody else. So far, we have managed. We are trying not to panic because it all starts with panic, and before you know it, the flights stop coming. Mykonos is resilient to all sorts of crises. Mykonians used to be the poorest Greeks, they worked hard for their riches, and they don’t want to ever be poor like their grandfathers.”

All around us, happy patrons lounged and danced against the golden sky and blue sea. “That’s what we offer, a good life, and it is our responsibility to keep people happy,” he continued. The DJ pumps up the volume while the crowd goes mad over J.Lo’s appropriate anthem — “I wanna dance and love and dance again!” Stehr has to raise his voice. “Even though it looks easy, it is not,” he adds. “There is no free money. Anything that stands here, it has been earned.”

Σχόλια για αυτό το άρθρο